Is NHS Implosion by Covid a Myth?

Dr No wrote this post (starting at paragraph 2) yesterday — and what a difference a day makes in covid. Overnight, news has broken of catastrophic worst case scenario predictions from the government’s pandemic modelling group SPI-M for the coming winter, with [enter your own choice of a large number here] deaths possible unless radical measures are taken immediately. Headlines vary in their degree of certainty, but the general message is that Boris Johnson is set to announce a national four week lockdown on Monday. Dr No takes a dim view of these hysterical worst case scenario predictions, viewing them as nothing more than Ferguson Reloaded. Though not yet fully in the public domain, some un-referenced blurry details have emerged, along with a completely unintelligible ‘surge capacity is burnt through’ Cabinet Office ‘timeline’ chart of hospital overload based on the SPI-M modelling, which once again suggest yet more modelling on steroids. Despite the appearance of these dire predictions this morning, Dr No continues to believe the NHS is not at risk of imploding by what the Cabinet Office calls ‘Xmas week’, and so publishes the post now as it was written yesterday.

One of the chief stimulants of covid hand wringing and bed-wetting is the fear that the NHS will be overwhelmed by covid patients. Fuelled back in the spring by heart wrenching images of Italian hospitals imploding, and given dubious backbone by the bizarre Stay Home – Protect the NHS – Save Lives mantra, the government wanted us to believe that the NHS was like a wicker bridge suspended over a deep ravine, already straining at its anchors, and sure to collapse if too many people jumped on it at the same time. It still wants us to believe that, as the winter pressures mount and expected seasonal covid admissions start to increase.

All the while a rather different picture emerged. One in which wards lay empty, and hospital staff relieved their boredom by making tik tok videos. One in which GP surgeries all but closed, and while some GPs showed themselves to be nimble, as they adapted to new ways of working, others rather less commendably enjoyed developing new ways of putting their feet up. One in which the new Nightingale hospitals, set up to accommodate the NHS overflow, all but remained empty. In this different picture, large parts of the NHS, far from being overwhelmed, were lying idle, ticking over in neutral, and about as likely to implode as a granite tor on Dartmoor. Nor was this idleness innocent. The absence of normal activity meant sharp and visible rises in non-covid morbidity and mortality. In this different picture, not only did the NHS not need protection, it was signally failing in its duty to protect the public from the burden of non-covid illness.

Of course, both pictures can coexist. One ward might be overwhelmed, while another down the corridor lies empty; but overall the NHS is not overwhelmed. Dr No’s experience is probably akin to that of many: he suffered the minor inconveniences of cancelled routine hospital and dental appointments, but at the same time received exemplary care from his available throughout GP. But one person’s experience does not give the fuller picture, so what do we find if we look at the figures?

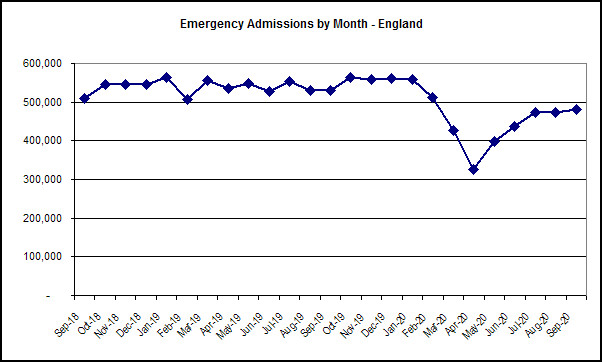

One measure of hospital implosion is emergency admissions. To put it bluntly, you can’t overwhelm a hospital without admitting a lot of patients, and we already know elective admissions were severely cut back, so we need to look at emergency admissions. The government’s coronavirus dashboard has a record of daily covid admissions by country, and NHS England makes available monthly data for emergency admissions. The latter show the striking effect of covid on emergency admissions: a dramatic fall in February to April, then some recovery, but emergency admissions are still significantly low. In September, there were 479,800 admissions, down 50,103 (9.5%) from 529,903 in September 2019. Figure 1 shows the picture.

Figure 1: Adjusted (for CRS Pilot sites, whatever that means…no obvious link to any methodology) monthly emergency admissions in England for the last two years. Source: NHS England.

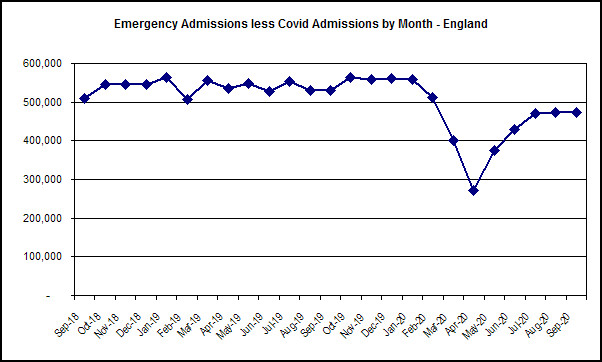

Now, on the face of it, if the NHS had getting on for 10% less emergency admissions last month than it did a year ago, it is hard to see how that means it is overwhelmed. Factor in reduced non-emergency activity, perhaps by as much as 50%, and it seems even less likely. If we then allow for the fact the emergency admissions will include covid admissions, we can see that at the peak of the first wave in April, the number of non covid emergency admissions all but halved compared to normal emergency admissions. Figure 2 shows emergency admissions with covid admissions removed.

Figure 2: Adjusted (for CRS Pilot sites, whatever that means…) monthly emergency admissions less covid admissions in England for the last two years. Source: NHS England and coronavirus dashboard. Note: data for 1st to 18th March are estimated.

The bottom line, given steep falls in both elective and emergency admissions, is that at no time was the NHS as a whole — Dr No accepts there were and are pockets of extreme pressure, but these were localised and limited — overwhelmed. In fact, the opposite happened: it was underwhelmed, with the dire consequence that many non-covid patients suffered worsening health and in extreme cases avoidable deaths because the NHS was running at historically low capacity. The awful reality, seen in the harsh light of hindsight, is that, by protecting the NHS, we prevented the NHS from protecting us.

Ah, you say, but what about ITU capacity – surely that was overwhelmed? In fact, it wasn’t. A report from the National Audit Office gives the figures (emphasis added): ‘NHSE&I data indicate that in total, around the peak of COVID-19 hospital admissions on 14 April, NHS providers in England had 6,818 ventilator beds operational, of which: 2,849 were occupied by COVID-19 patients; 1,031 were occupied by other patients; and 2,938 were unoccupied‘. The report concludes that ‘In the event, the new ventilators were not needed at the April peak because demand was considerably lower than the reasonable worst-case scenario‘.

That is what happens. The numerology predicts catastrophe, and then reality happens: at the peak, only 57% — less than two thirds — of ventilator beds in England were occupied. As of the day before yesterday, 803 covid patients in England were on ventilators, compared to just under 3,000 back in April. Ventilator capacity was nowhere near being over overwhelmed in April, and is even less under threat today.

As the winter pressures mount, as they surely will, there is going to be an orgy of hand wringing and bed-wetting about hospital capacity and deaths. When cases started to surge in the spring, we had the excuse that covid really was a new disease, about which we knew very little, and so a little hand wringing and bed-wetting was understandable, if unfortunate. This time around, we have no such excuse. We have a stronger NHS, a better understanding of both the disease and how to treat it, and the hard data from the spring surge. Current data, as it comes in, tells us the current expected seasonal surge is happening, but at a slower rate than in the spring. The NHS didn’t implode in the spring and over the summer — the reality is in fact the opposite, it underperformed, and as a result many suffered and died from non-covid disease — and there is no sound reason to believe the NHS will not manage this winter’s rise in cases. Instead of yet more hand wringing and bed-wetting, what we really need is more hand washing and bed making.

‘The awful reality, seen in the harsh light of hindsight, is that, by protecting the NHS, we prevented the NHS from protecting us.’

Dr No has nailed it.

I so hope many read this, see the figures here, and not those plucked from the air and which litter the ground everywhere else. Thank you for this (very!) timely post.

But, but, but … haven’t you seen HMG’s graph showing that admissions for respiratory infections are running at thee times the usual for this time of year?

No, neither have I, which presumably means that there’s nothing unusual about the admissions rate. Which means that Boris is being a big sissy again.

It seems pretty clear by now that, medically and scientifically, Covid-19 is no worse than a bad seasonal flu. In some ways it is much better (or less bad) in that it mainly kills those who are already at death’s door – meaning that it affects the young and healthy far less.

Politically, Covid-19 has taught us all some bitter lessons that we should have understood decades ago.

First, it’s wrong in principle to allow politicians, bureaucrats and business people to interfere with medical care and scientific research. This year we have seen a whole series of appallingly wrong decisions made by people who were utterly unqualified to make them. Perhaps even worse, we have seen decisions made as a result of “misunderstandings”: the politicians ask the scientists what will happen, and the scientists come back with a “reasonable worst case scenario”. In meteorological terms, a “reasonable worst case scenario” might be that we shall be struck by a large comet. Then the politicians unquestioningly accept the “reasonable worst case scenario” and behave as if it were a confident prediction of what will happen. Everyone is concerned about covering their backsides and protecting their reputations and incomes. Nobody is in the slightest concerned about the public good.

Second, the whole concept of the NHS has been shown up as intrinsically faulty. It suffers from giantism, which leads inevitably to the cancer of bureaucracy, with administrators and politicians telling doctors how they may and may not treat their patients. On of the many fatal consequences is a mania for cheese-paring. In order to free up the billions that are urgently required for administrators’ plush offices, expensive cars, mansions, costly suits and absurd perks, such unnecessary luxuries as beds, doctors, nurses and equipment are ruthlessly cut back to the absolute minimum – in a good year. Then when a bad year comes along, there is wailing and gnashing of teeth that “our precious NHS may be overwhelmed”.

Tom De Marco’s excellent book “Slack”, which should be required reading for… well, everybody, explains in words of one or two syllables how foolish it is always to be cutting costs to the very bone, and how that actually costs far more in the medium term (let alone the long term).

As for the NHS, it – like the US system – is fundamentally misconceived. We need to start by reassessing our values and goals, and reminding ourselves that the health of patients is the only goal of a health system. Other considerations, such as cost, are subsidiary to that overriding goal.

So we should go back to a system of health care that is as distributed and local as possible. As for the administrators, every single one of them should be fired. Maybe they can get jobs as janitors, or maybe not. Everything can be run by doctors and nurses in their spare time. They are very clever, hard-working, responsible people.

“Everything can be run by doctors and nurses in their spare time.”

That reminds me of my primary school. The Principal taught a full class and did his principalling after we’d all gone home. During the day the admin burden was bravely borne by his whole management team i.e. the secretary and the janitor.

Neither in primary or secondary school can I remember the existence of a Deputy: I have no idea who took over if the Principal had a flu.

All that was changed by The Forces of Progress, eh?

“Everything can be run by doctors and nurses in their spare time.”

Perhaps that looks flippant or foolish. On the contrary, getting rid of all the administrative deadwood would not only save tons of money, but free up space and time, and allow decisions to be made far faster and more rationally.

If the medical staff is not big enough to allow some doctors and nurses to do administrative work, the answer is simple: hire more! There should be masses of resources sloshing around once the cancer of administration has been defeated.

Unfortunately, it has been said that no one has ever been able to eradicate a full-fledged bureaucracy with the single exception of Genghis Khan. His method was startlingly simple: kill every last bureaucrat and burn all their files. (But it was vital not to miss a single one, or the whole mess would start again).

It’s becoming ever more clear that the actual book to read – as a dire warning – is ‘Covid-19 The Great Reset’ by Klaus Schwab and Thierry Malleret. And it’s not about saving people or our planet, whatever its ‘sales pitch’.