As A Precaution

The higher one lies in national life, the more one suffers from the indignities of precautions. When Prince Philip drives his Range Rover over a cliff top at ninety miles per hour, does three full somersaults in the air before landing wheels down in the water, and drives ashore as smooth as James Bond, he nonetheless gets taken to hospital ‘as a precaution’. When the Prime Minister’s covid-19 symptoms failed to settle he was admitted to hospital ‘as a precaution’. Eminent doctors were on hand to speculate as to what tests might be done on the PM, purely as a precaution. Then the PM was admitted to ITU ‘as a precaution’; but happily the tide turned, and Mr Johnson was soon back on the wards. In the last few hours, Mr Johnson has been discharged from hospital, and Dr No wishes him a full recovery which, as his father Mine’s-a-Pint Stan, never one knowingly to keep his mouth shut, has already observed, may take some time.

The immediate effect of putting the head of state in hospital was to create a vacuum at the top. Luckily, contingency plans were in place. Dominic Raab, the Foreign Secretary, was screwed into place, much as one might change a light bulb. The lights were back on, power restored. Or was it? At the risk of flogging a dead horse, the question now arose, yes, the lights are on, but is there anybody at home?

It seems not. The office of Foreign Secretary is one of the choicest in the land, yet one struggles to remember an incumbent who has glowed in the post. Instead, shadows from the past play on the mind, even from as far back as the Fifties, when Eden blew Suez. Since then, a string of unmemorable aesthetes have not quite coped with Imperial decline, with events all too often being marked by rushed barely adequate not quite in time last minute evacuations. Little surprise then that much the same has happened in the current crisis.

One effect of the lights being on, but there’s nobody at home, has been a weaselling out from tomorrow’s planned review of the lockdown, originally planned to take place three weeks after the introduction of the measures. This is misguided in the extreme, for it reminds us, if reminding is needed, that governments can say they will do one thing, and then do another. It also shows us, if showing is needed, that we lack leadership. The strong leader leads, and decides, the weak leader, or worse, the committee, prevaricates, and defers.

And yet, over these last three weeks, while we have seen the flowering of ever more imaginative numerology, with a model for every conceivable scenario, we have also seen the slow but relentless accumulation of real data. The data, which are steel plate to the tissue paper of models, are nonetheless far from perfect, as national testing and reporting habits vary greatly. There are confusions between the infection mortality rate, the rate of death in all, whether formally diagnosed or not, infected people, and the case fatality rate, the rate of death amongst those with a positive covid-19 diagnosis. Further confusions stem from varying enthusiasms for assigning covid-19 as the cause of death, with some nations adopting a you can have any respiratory cause of death you like, so long as it is covid-19, to others taking a more nuanced approach.

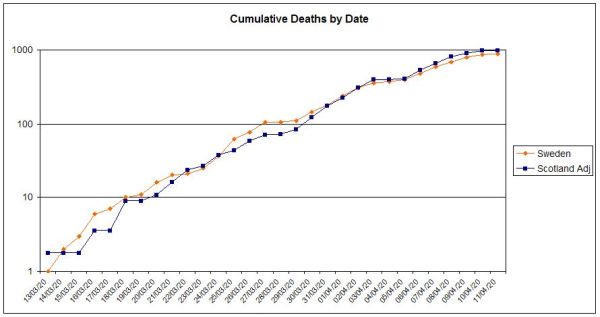

With these important caveats in mind, what does the less than perfect data suggest? There’s a lot of it about, as we medics say, so Dr No is going to select a ‘natural’ experiment, so-called because they happen naturally, by accident, as it were, rather than being deliberately set up. Let us take two smallish North European nations that may or may not have much else in common except a liking for blue in their National flags, Scotland and Sweden, and compare their cumulative daily covid-19 death totals. The natural experiment part, which is why Dr No chose these two nations, is that while one has a strict lockdown, the other has a laissez-faire approach bordering, some suggest, on the reckless.

What we find is rather interesting. It helps that in both nations, deaths started to increase at similar points in time, so we don’t need to do any of that days from so many deaths jiggery pokery. The populations are small, but not the same, so Dr No has adjusted the Scottish death numbers as if Scotland had the same population as Sweden, this being simpler and more easily visually grasped than doing a plot of adjusted rates ie deaths per million. The plot of the daily cumulative numbers of deaths so adjusted speaks for itself:

Figure 1: Cumulative covid-19 deaths by date for Sweden and Scotland, after adjustment for population size. Deaths plotted on a log scale, which transforms exponential curves into something closer to straight lines, and makes them easier to compare. Data sources: Sweden: JHU Scotland: Scottish Government via Wikipedia.

Now, this natural experiment is not a randomised controlled trial, it is not even a trial, but it is real data, and numerology free if we allow the adjustment of the Scottish numbers as a reasonable ruse (all that happens if you remove it is the Scottish line sits a bit lower in the plot). Notwithstanding any other differences, from population age distribution to health care provision, the two lines are remarkably similar, despite the fact the two nations adopted radically different lockdown policies.

The British nations brought in their lockdowns, as a precaution, based on numerology. Before we had any real data, no one knew what was going to happen, only what might happen, if the models were right, the moon was in Virgo, and we did this or that. Dr No might even allow it was not unreasonable, in the face of such overwhelming uncertainty, to adopt initial radical lockdown measures ‘as a precaution’. But that was always done on the understanding that there was provision for early review in the light of emerging data.

The collapse of the singular office of Prime Minister, and its replacement by deputies and committees, has compromised leadership at a time when it can least afford to be compromised. One casualty of this collapse and compromise has been the much needed review planned for tomorrow. The last three weeks have shown us all very clearly the harms that lockdown does, with worse yet to come as the effects become entrenched. We have, by and large, grudgingly tolerated this dystopian state of affairs as not necessarily unreasonable given the early uncertainty.

Now, three weeks down the road, we have more data, including some that suggest that the efficacy of all but universal lockdown might not be all it was cracked up to be. At the very least, the government needs, as a precaution against a charge of favouring numerology over data, to assess all the available data, and revise it’s policies as best it can in the light of the emerging data, if its cry that it is ‘led by science’ is to have any chance of remaining credible.