Obvs Innit

If you asked a group of people whether making wearing front seat belts in cars compulsory helped save lives, many would answer in the affirmative. Ask how they know the answer, and many will say some variant of obvs innit: it’s obvious, it stands to reason, it’s common sense. The law, when it came in, in January 1983, was hugely controversial, but the controversy wasn’t about effectiveness, it was about liberty. It was the first time the government had passed a law that sooner or later would affect just about everyone, requiring them to do something not to protect others, but to protect themselves. Since we were at the time, and still are for matter, free to drink ourselves to death, or smoke ourselves to death, it was argued we should also be free to smash ourselves to death. The state had no business interfering in personal decisions; doing so marked the beginning of the nanny state, from which there would be no turning back. Promoters of the law claimed that up to a thousand lives be saved every year, and there would be important secondary benefits, including reduced demand on the NHS.

These and similar arguments are of course familiar today, in the debates of lockdown regulations and mask mandates. Back in 1983, the slogan could easily have been Belt Up, Save Lives, Protect the NHS. Today’s covid version we all know only too well. And again if we were to ask a group of people today whether stay at home should be made compulsory, or masks mandatory, many would reply yes, obvs innit. A similar debate is brewing over compulsory vaccination: first it will come for the health and social care workers, then it will come for other front line workers, until all are vaccinated. Get Jabbed, Save Lives, Protect the NHS.

The key point here is compulsion. This post is not about whether seat belts, lockdowns, masks and vaccinations work in and of themselves, it is about whether making such measures compulsory adds anything. Here, the introduction of compulsory front seat belt wearing provides a unique opportunity for a before and after study: a single law altering a single behaviour coming into force in a single day. If compulsion works, we should see an almost overnight benefit, and annually up to a thousand lives saved. We will stick with just lives saved, for familiar reasons: death counts tend to be reliable, even over decades, whereas injury data, especially hospital episode data from the past, tend to be notoriously unreliable.

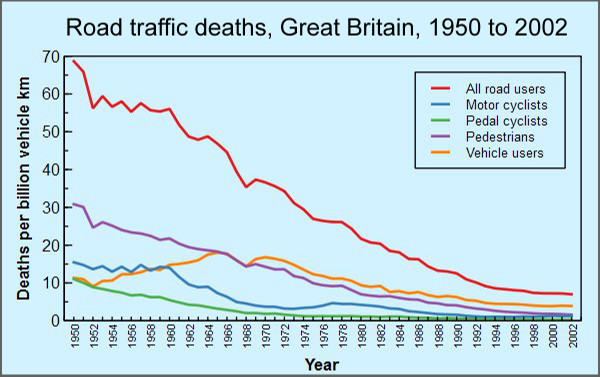

Compliance with the new law was excellent. Seat belt use by drivers and front passengers rose quickly from around forty percent to well over ninety percent. Behaviour certainly changed, but what about road traffic deaths? Here we are lucky in that a long running Department for Transport data set got tucked away on the Wayback Machine. It covers the half century from 1950 to 2002 (with a methodology change in 1993 that need not bother us) and annual road traffic deaths for all road users and for each of the major classes of road user. It also very usefully includes estimates of annual traffic, allowing calculation of deaths per billion vehicle km travelled, to allow for changes in road use over the period. Figure 1 shows the results.

Figure 1: Road traffic mortality per billion vehicle Km, Great Britain, 1950 to 2002

Is there a readily visible drop in mortality caused by the introduction of compulsory seat belts for drivers and front passengers? According to the Road Safety Observatory, we should see ‘an immediate 25% reduction in driver fatalities and a 29% reduction in fatal injuries among front seat passengers’ in 1983. But we don’t. There is a very minor kink in the orange line (vehicle users) in 1983, but this disappears in the red line (all users). There is certainly no immediate 25-29% reduction in deaths, nor is there the ‘up to a thousand’ front driver and passenger lives saved — which would amount to a 40% or so reduction in deaths — promised by the Secretary of State.

The only and unavoidable conclusion is that compulsion had no discernable long term effect on deaths. There was a wobble in 1983, a small reduction in car user deaths, but with a year of two, deaths had reverted to their long term trend. All road user deaths didn’t even wobble, because 1983 saw an increase in pedestrian and pedal cyclist deaths. This isn’t very obvious in Figure 1, so here are the raw numbers (not rates) for the period 1981 to 1985:

| Year | Pedestrians | Pedal cyclists | Motor cyclists | Vehicle users | All deaths |

| 1981 | 1,874 | 310 | 1,131 | 2,531 | 5,846 |

| 1982 | 1,869 | 294 | 1,090 | 2,681 | 5,934 |

| 1983 | 1,914 | 323 | 963 | 2,245 | 5,445 |

| 1984 | 1,868 | 345 | 967 | 2,419 | 5,599 |

| 1985 | 1,789 | 286 | 796 | 2,294 | 5,165 |

Table 1: Road traffic deaths, 1981 to 1985

This unwelcome temporary increase may even have been caused by compulsion, by way of risk compensation, the process whereby individuals adjust their behaviour on the basis of perceived risk to remain at the same overall level of risk. Car drivers, believing themselves safer because they were protected by seat belts, drove a little more recklessly, and as a result killed more pedestrians and pedal cyclists.

The bottom line, or rather the top line in Figure 1, shows that compulsion to wear seat belt had no discernable effect on road traffic deaths. That does not for a moment mean seat belts don’t work. They clearly do — obvs innit — and will, along with many other measures, have contributed over the years to the welcome decline in road traffic deaths seen over time. The lesson here is that compulsion doesn’t add anything.

Since 1983 until very recently, there have been no mass effect public health laws that have required individuals to change their individual behaviour. With the arrival of covid–19 last year, that changed very rapidly, and we were all very soon up to our necks in just such public health laws, requiring extraordinary changes in behaviour. Yet the lesson from 1983 is that compulsion may not add anything at all to the mix. Add the very distinct possibility that neither lockdowns not masks work, and the already flimsy case for compulsion collapses entirely. Obvs, innit.

Fascinating correlation, Dr No, thank you! I was really surprised; being ‘of the time’ and thus expecting a steep plummet that year. As you say, seatbelts have surely saved a life or three, but not the compulsion. What, surely, has made a difference is safer cars, safer roads (sorry to use that damned ‘s’ word), which in human terms in our insane ‘now’ surely means a supported immune system, healthy food, enough exercise, reduction in toxins (many, various, and subjective, of course), and plenty of fresh air, hugs, and human interaction, service, and play. Yet, using your analogy, cars’ technology worsened, MOT’s banned, roads fell apart and signage was abandoned, but with everyone belted-up, the death figures would still surely drop. Obvs, innit. Not.

(And, no, I won’t be applying for a prize for more ‘surelys’ than even I thought possible in so few words?!)

At the time of the introduction of compulsory seat belts, there was a tongue in cheek suggestion that the same effect might be achieved by installing a sharp spike in the steering wheel. This spike would shoot out towards the driver’s chest in the event of an accident, in the way that airbags deploy.

It was argued that the prospect of being impaled in this way would concentrate drivers’ minds and their driving would become safer. I think it might have led to a reduction in accidents, and possibly a reduction in damage to cyclists and pedestrians. Being cocooned in a steel cage with airbags and seatbelts must subconsciously make you believe that you are completely protected and will survive any accident.

It would be interesting to see data on the number of collisions per km over the years to see if there was an increase in collisions involving motor vehicles.

“It was argued that the prospect of being impaled in this way would concentrate drivers’ minds and their driving would become safer”.

While such a measure might have helped to focus drivers’ minds, it would have made little practical difference. I remember vividly reading (about 55 years ago) an article in “Reader’s Digest” that described the exact sequence of events in a car crash, millisecond by millisecond. I recall the sharp stab of (almost physical) pain I felt when reading how, after a fraction of a second, the driver’s forward plunging chest would be impaled by the steering column.

Consequently, when seat belts became compulsory I became a convert to “clunk-click every trip”. (One very good thing Jimmy Savile did).

It certainly seems pretty clear that Jimmy Savile’s Clunk-Click ads, which began in the early 1970s, helped lay the ground for the seat belt law, but I don’t think I’ve seen anything to suggest he, himself, supported the introduction of a law. I would be most interested if anyone knows whether he did.

Another good thing Savile did was, erm, support our NHS, and encourage many others to do the same through charity endeavours. Most impressively, he raised the funds for, and built, the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, though it seems he was reluctant to hand control of the centre to the hospital trust, ultimately resulting in considerable animosity.

The madness of the past year is perhaps the first such to surpass the year in which everyone discovered that they’d always known Sir Jimmy Savile was a monster and, in very many cases, remembered that they’d been abused by him.

It certainly seems pretty clear that Jimmy Savile’s Clunk-Click ads, which began in the early 1970s, helped lay the ground for the seat belt law, but I don’t think I’ve seen anything to suggest he, himself, supported the introduction of a law. I would be most interested if anyone knows whether he did.

I’m sure he didn’t, but he never shied away from the reflected light of a good cause.

Another good thing Savile did was, erm, support our NHS, and encourage many others to do the same through charity endeavours. Most impressively, he raised the funds for, and built, the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, though it seems he was reluctant to hand control of the centre to the hospital trust, ultimately resulting in considerable animosity.

Something, given his ample political connections, he could have quietly lobbied for.

Why should a tv personality have ‘control’ of a specialist spinal unit anyway?

The madness of the past year is perhaps the first such to surpass the year in which everyone discovered that they’d always known Sir Jimmy Savile was a monster and, in very many cases, remembered that they’d been abused by him.

No prime minister or monarch (some living, mostly dead) in a photo with him has ever made that claim.

Dr No will I’m sure be aware that the passing of the law requiring motorcyclists to wear safety helmets had, in part, been based on a promised reduction in deaths. This article on The Motorcycle Helmet Law discusses some of the arguments.

Surely the argument for vaccination is strengthened by the claim that increased levels of immunity within the herd reduce the chance of transmission, bring forward the day when the virus dies out, and reducing the likelihood that those unprotected (either those unfit to be vaccinated or those for whom the vaccine fails) will be infected. The previous sentence may need about three ‘Obvs Innits’, not least for the fact that no vaccine, as far as I’m aware, has been tested for its capacity to reduce transmission, but the assumption is that if it reduces illness it must somehow reduce transmission.

This argument looks worryingly likely to persuade a public which has been so happy to wear its masks to protect others, and be seen doing so.

As always, an excellent piece, but it doesn’t help. I am in despair. Everywhere I go I’m seeing muppets wearing nose bags, crowing about how they’ve “had their jab”. If I ask them how they feel about being injected with something for which phase 2 clinical rials won’t be completed for another 2 years, I’m met with a blank stare of hostility or I’m told that I’m a “covidiot/anti-vaxxer/conspiracy-theorist . . . .”.

My immediate neighbours are of this mind – and, a few months ago, were even out banging on saucepan lids applauding the abject systemic failure of the NHS.

Meanwhile, draconian laws have been nodded through that will prevent questions from being asked, let alone discussed or debated. Nowhere is there an effective opposition – the rosette colour is irrelevant. If I lived in London, I’d vote for Lawrence Fox as mayor (another daft idea) but fear it would be pointless. I’ve lost faith in all British institutions & would guess that the election outcome has already been rigged in favour of the ruling establishment’s favourite puppet.

In the 1930s, smart European Jews had various places they could run to. We don’t because C19 thing is a global racket. What to do?

Transfer of risk. The politician’s favourite: ‘unforeseen consequences’, the result of lack of consideration of the unseen by not the brightest minds in thrall of their own clever idea.

One of the consequences of front seat passengers wearing seat belts was back seat passengers catapulted forward in a crash smashed face-first into the back of the heads of front seat passengers, the which heads without restraint would have been forward smeared on the dashboard or windscreen, but now were recoiling back into the forward travelling faces of the unfortunates from the back seat.

It is partly why in-vehicle deaths did not change, death and injury were transferred from front seats to back seats, and front seat passengers got their head injuries from back seat passengers instead of windscreen, dash or steering wheel.

In additional whiplash injury caused by seatbelts caused spinal injuries and fatalities.

This all led to head restraints, rear-seat belts and air-bags.

So, if we follow that example will we end up with multiple vaccinations for every variant that inevitably evolves, continual medication with antivirals and antibiotics for good measure (because getting anything infectious makes us murderers) and full HazMat suits in due course?

There is also another factor – diminishing returns, output is logarithmic and (like terminal velocity due to gravity) a point is reached where no matter what the input, the output does not change.

We hear this repeatedly about drink-driving, which refuses to go down to zero leading to calls for even stricter limits. Which brings us back to CoVid… no matter how many vaccinations and Mask Zombies stalk the realm, deaths and infections will just will not reduce to zero, so more must be done.

“it stands to reason” is a statement in idiomatic English that means “neither logic nor evidence support my point”.

Exactly, dearieme. Many of Richard Feynman’s superb distillations of the nature of science say just that.

“Obvs, innit” represents a useful human reflex; without it we would be floundering in a welter of events, unsure what to do at every moment.

But science could be defined as the methodical rejection of “obvs, innit” in favour of experimentation. We do best to find a suitable balance between the two: “obvs, innit” suffices for most of ordinary life; but when the stakes are high and time permits, it’s always wise to check.

In the hope that I haven’t cited it too often, here is a useful thought from that trained engineer, the SF writer Robert A. Heinlein:

“If ‘everybody knows’ such-and-such, then it ain’t so, by at least ten thousand to one”.

– Robert Heinlein, ‘Excerpts from the Notebooks of Lazarus Long’, “Time Enough for Love”

I give you the Clean Air Act of 1956. Everyone knows that it reduced atmospheric pollution: stands to reason. But Bjorn Lomberg pointed out in The Sceptical Environmentalist that the curve showing the decline in air pollution over the years exhibits no change corresponding to the introduction of the Act.

Not that that will stop the indoctrination of schoolchildren on such a Green law. Green = good: obvs innit?

Thanks ever so much for that graph, Dr No. A real eye-opener, and one that I absolutely did not see coming. Very much like the graphs of deaths from infectious diseases, on which one can usually not tell at which point the corresponding vaccines were introduced. Or antibiotics.

When seat belts were made compulsory, I belted up with everyone else. The law, and the very good TV ad with Jimmy Savile and the catch-phrase, “clunk click, every trip”, persuaded me.

The only reservation I felt – and still do – was about the occasional person who dies because they are wearing a seat belt. They are trapped in a burning car, for instance, and the seat belt mechanism jams.

It sticks in my throat that even one person should die miserably because of something the law commanded him to do.

Deaths and serious injury from vaccines, of course, are far more common.

Thanks you all for your comments.

The inflatable elephant that has suddenly popped up in the room over the last 24 hours is BoJo’s apparent U-turn on vaccine passports. From what he said at the Liaison Committee meeting yesterday, once you have got through the waffle, it appears to be classic flock leading the bellwether rather than the other way round. On vaccine certificates he had this to say:

“I find myself in this long national conversation, thinking very deeply about it—I think the public have been thinking very deeply about it—and my impression is that there is a huge wisdom in the public’s feeling about this. Human beings instinctively recognise when something is dangerous and nasty to them, and they can see, collectively, that covid is a threat. They want us, as their Government, and me, as the Prime Minister, to take all the actions I can to protect them. That is what I have been doing for the last year or more.”

In other words, if the Joe Public wants vaccine passports, the Brother Jo will provide. Further evidence, were further evidence needed, that the move to No 10 turned Brother Jo into a radio-controlled bellwether under the direction of the flock came from a backbench Tory on WATO this lunchtime, who averred that a back bench Boris would vehemently opposed any such authoritarian moves.

The motor cycle helmets law was indeed in the first draft, but the post started to morph into “Enoch Powell and the Rivers of Cerebro-spinal Fluid” and given that the law only affected a minority of road users, it got left out, even though the liberty/nanny state arguments were very much there. The seat belt law on the other hand was a mass effect public health law that sooner or later would affect just about everyone’s behaviour, in much the same way that lockdown rules and mask mandates have done.

Nonetheless, it is worth perhaps quoting Powell briefly, talking here about the beguiling nature of saving fellow people from their foolish actions:

“But that is where the danger lies. The abuse of legislative power by this House is far more serious and more far-reaching in its effects than the loss of individual lives through foolish decisions. I say just that and I repeat that, as a Member of the House of Commons speaking to the House of Commons. The maintenance of the principles of individual freedom and responsibility is more important than the avoidance of the loss of lives through the personal decision of individuals, whether those lives are lost swimming or mountaineering or boating, or riding horseback, or on a motor cycle.”

How times have changed.

The sharp spike in the centre of the steering wheel also made a brief appearance in the earlier draft. A casualty consultant Dr No worked for in the late 1980s (so after the seat belt law) was a very keen proponent of a very simple implementation: no mechanism, just a spike of toughened steel with the tip pointing at the left ventricle. Dr No inclines to the view such a device might well work, since the only available risk compensation measure is to slow down. Another candidate is packing the front bumper with high explosive with a pressure sensitive fuse, but that might give new meaning to ‘I’m just going drop into Sainsbury’s to pick up some milk’ if one accidentally bumped a rogue trolley while parking.

Yet another thing that got spiked was a discussion on how difficult it is to prove a legislative measure works or doesn’t work. Since it is already written, here it is:

“Yet things are hardly ever that straightforward. A single legislative measure never happens in isolation. Other factors — population size, demography, climate, pollution levels — are all in a state of flux; and to pile Pelion on the investigating epidemiologist’s Mount Ossa, people change. Human behaviour is complex, perhaps even chaotic, as the flutter of a mandarin’s wings in Whitehall causes an unexpected ripple in the Outer Hebrides. In this sea of complexity, proving that Law A led to Outcome B is indeed complex…”

The seat belt law, on the other hand, was a single measure introduced on a single day that affected everyone, and compliance was demonstrably high. It is about as close as you can get to an ideal before and after observational experiment, which makes it worth looking at in some detail.

The next Great Compulsion is surely going to be the introduction of domestic vaccine passports. The tide is on the turn, from why should we have vaccine passports, to why shouldn’t we have vaccine passports. The authoritarian implications are enormous.

I omitted to day in my earlier post that the fatal drawback of the steering wheel spike concept, is that a perfectly innocent driver who is driving safely may suffer a head-on collision with a dangerous driver and both drivers then die of impalement.

I used to think,when watching Volvo’s adverts which emphasised their cars’ s safety, that it was slightly smug as their cars were heavy and more likely to cause severe damage to lesser vehicles.

The tail wagging the dog, for sure; BoJo wants to keep his ‘friends*’ off his back, and have the people like him – bless – so he’s doing what Joe Public wants, which is what Hat Mancock* has told them to want.

Yet, in 2004, Boris wrote in his blog::

“If I am ever asked, on the streets of London, or in any other venue, public or private, to produce my ID card as evidence that I am who I say I am, when I have done nothing wrong and when I am simply ambling along and breathing God’s fresh air like any other freeborn Englishman, then I will take that card out of my wallet and physically eat it in the presence of whatever emanation of the state has demanded that I produce it.

If I am incapable of consuming it whole, I will masticate the card to the point of illegibility. And if that fails, or if my teeth break with the effort, I will take out my penknife and cut it up in front of the officer concerned.”

(Full blog here: https://www.boris-johnson.com/2004/11/25/id-cards/ )

We’re up against something deeply worrying now… and it’s happening awfully fast…

Do not take it personally,or be surprised.

He, and his expanding family,will not do it, but is happy to see all beneath him conform.

What happened in 1968? Big drop in motor vehicle casualties from the mid 60s until 68?

Adamsson – generally thought to be the crack down on drink driving. In fact the ongoing crack down may also be a confounder in the 1980s. For example it has been argued that the 1983 small dip in deaths was more due to changes in drink driving behaviour than the introduction of compulsory seat belt wearing.

Important not to lose sight of the central point of this post, that the introduction of compulsory front seat belt wearing did not bring about the predicted fall in road traffic deaths. Compulsion doesn’t work. With that said and done, there is a rich seam of historical data to be mined as to what has actually caused the long term decline in deaths, and that despite year on year increases in vehicle miles travelled.

The recent Council of Europe resolution 2361 (Covid-19 vaccines: ethical, legal and practical considerations) is clear –

“The Assembly urges member states to ensure that citizens are informed that the vaccination is NOT mandatory and that no one is politically, socially, or otherwise pressured to get themselves vaccinated, if they do not wish to do so themselves;

…

“ensure that no one is discriminated against for not having been vaccinated, due to possible health risks or not wanting to be vaccinated”

The past twelve months have shown just how easily all those protections which were supposed to have been afforded us by the various post-war agreements such as the Convention on Human Rights and the Nuremburg Convention, not to mention this latest CofE resolution, can be so easily swept aside and rendered nugatory. What was the point of these protections if they can be rendered ineffective just at the time when they are most needed?

I’m still alive because I wasn’t wearing a seatbelt when my 1972 lwb landrover cut the back corner off a Ford focus, the driver of which had just pulled across me turning right out of a side road.

I hit the car side on just behind the rear door at around 60mph. The Landrover cleaved the back third of their car off, then flung it up the bank at the side of the road, then emerged the other side at about 40mph… As the wreckage of the Focus scraped down the side of the Landrover, the outside seat belt mount on the drivers side was dragged about a foot back down the side of bodywork – had I been wearing the belt, it would have cut me in half.

As it was, I successfully brought the Landrover to a controled stop a hundred yards down the road (one burst front tyre made applying the brakes tricky), and drove home after the police had let me go, having straightened out the front bumper enough to get the spare wheel on. The Focus driver was very shaken, and probably had shocking whiplash (the wreckage had spun pretty violently after the Landrover had finished with it), but was otherwise OK. I wasn’t even stiff.

There is probably a bet benefit to wearing belts in modern vehicles, but I wouldn’t wear them in a vintage Landrover (I think at least up to 2005 defenders the outer front belt anchors are all attached the same way)

I’m coming to this rather late but I’m afraid I don’t necessarily agree with your interpretation of the seat-belt data Dr No. The law may have changed on a single day, forcing nay-sayers like my father (a mechanical engineer) to wear them, but there had been a long term change in behaviour as new cars began to be standardly fitted with seatbelts from the late 60s and a few higher end marques had seat belts before that. This might arguably be consistent with the downturn in deaths from the mid 60s, following a rise during the 50s. I do agree one might then expect a precipitous dip in the early 80s but there are big confounding variables that were introduced at different times such as changes in the cage structures of cars that made them safer, introduction of motorway speed limits and – in the other direction – an increasing density of road use by domestic cars and freight that probably increased the risk of accident per kilometre travelled.

Hippocentaurus – thanks for your comment and no problem coming to this rather late, one of the reasons for using a blog rather than twitter is it avoids the transcience of the latter. Things also stay in their right places, rather than being jiggled by twitter’s topsy turvey idea of time.

There are certainly a lot of potential confounders, that much can be seen from the longstanding downward trend in mortality. It is also true that a before and after comparison like this is never going to prove causation, that the seat belt law lead to a drop in mortality, given that association is not the same as causation. But what we are doing here is trying to do here is in fact rather the opposite: see that something didn’t have an effect; and if nothing else, if nothing happened, no question of causation arises, if that makes sense. We are just looking at the data to see if something didn’t happen.

The most likely significant explanation for the 1960s fall in mortality over and above all the other effects is the change in drink driving attitudes and laws. Moving on to the early 1980s, we can make a prediction: if the sealt belt law had an effect, over and above the other confounding factors, then we should see a significant and sustained drop in mortality. But we don’t. So either (a) the law didn’t have its intended effect or (b) something else happened to counteract a true fall in mortality caused by the law, of such a magnitude that it cancelled out the benefit. There is in fact a bit of this visible: the transient fall in vehicle user deaths and rise in non-vehicle deaths, with the overall deaths staying on a reasonably consistent trajectory.

The other interesting factor is the reports of seat beat use before and after the law coming into force on the 31st January, an almost overnight increase in front seat use from around 40% to well over 90%. In that sense the law did work, but it didn’t follow through into a matching decline in mortality. That part of the tale is harder to explain, with risk compensation being at least a plausible candidate. It would be interesting to see if speeding or possibly dangerous driving convictions went up in 1983, if such records exist, and hoping against hope there weren’t any major confounders, such as other changes in policy and/or the law.

The point about increasing traffic density of itself being a risk factor, over and above putting more people at risk, is an interesting one. If you double the number of person miles travelled, all other things being equal you will see double the number of deaths (but of course the same mortality per mile travelled). If the increased density of itself increases risk, then the rate (as well as numbers) should go up, but it/they don’t: so we are once again back to the many other factors that have, thankfully, helped reduce deaths on the roads.

But it still seems reasonable to make the central point of this post: that coercion doesn’t always (if ever) produce a predicted benefit (and so a case can be made for avoiding coercion, and relying instead on softer measures). That’s the key point: it is anything but ‘obvs innit’ that compulsion works.