Covid and Coercive Healthism

Perhaps the most putrid specialty in a profession that has more than its fair share of stinkers is public health medicine. A natural bunker for malfunctioning medical Mussolinis and failed physician Pinochets, public health medicine has evolved an alien and grandiose medical culture in which they who practice it are above mere patients. Instead, they have populations. Just as Mussolini engineered a society in which the trains ran on time, so public health physicians would have it that the population abstains from fags fizz and fornication, downs its five fruit and veg a day, and, armed with a faecal occult blood testing kit in its hands, opens its bowels on time. Their vision, like their ideological forebears, the Stalinists and the Nazis, is one of the nation state as a boot camp for health, a vast breeding ground for a pure population free of disease, infirmity and disability, all watched over by health marshals wearing caps emblazoned with the rallying yet blinding cry, Health for All, and All for Health! What could possibly go wrong?

Well, quite a lot, of course. This is the toxic world of health fascism, and its first, and in some ways more developed, cousin, coercive healthism. Health fascism is crude and brutal — the state knows best what is good for the health of the people, and the people must comply — but coercive healthism is subtler, in that it infects the people with a belief in healthism, the notion that the pursuit of health and longevity is a natural good in and of itself. If that was as far as it went, we might be prepared reluctantly to tolerate it, but healthism very quickly mutates into coercive healthism. The coercion comes in two ways. Instead of the people being free to chose whether they want to pursue eternal health and happiness — and in the process become the neurotic automatons of the worried well — the state imposes a moral duty to pursue eternal health and happiness. This duty is sold as benefit to the individual, but its true target is to benefit the health of the nation. This imposed duty then creates two classes: the good, who accept the imposition, even welcome it, and the bad, who reject it, and continue their wicked ways. This in turn leads to the second, more insidious and yet even more powerful coercion, that of the people on the people. Healthism starts to operate like any other ‘ism’, with those on the ‘good’ side marginalising, denigrating and attacking those on the ‘bad’ side.

None of this should come as any surprise, because coercive healthism has been on the rise for decades. We see it every time a Chief Medical Officer stands up and tells us we should drink less, exercise more, and keep slathering on the sun cream. The doctrine underpinning this approach — targeting the population rather than the high risk individuals — comes from a wily old London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Professor of Epidemiology, Geoffrey Rose. By far the most influential publications by Rose are a linked pair of papers, the first published in 1985 and chilling titled Sick Individuals and Sick Populations, and the second, published in 1990, and even more chilling titled The population mean predicts the number of deviant individuals. We can even see the dead hand of healthism at work in the titles: by 1990, 1985’s sick individuals had become deviant individuals, the bad individuals who have failed to embrace healthism.

In these papers, Rose advanced the notion, backed up by some between country comparisons, that average behaviour in a population — for example, average weight, or average alcohol consumption — determines the extremes — for example, obesity, or excessive alcohol consumption. Cleverly labelling any approach that targets high risk individuals, that is the sick and the deviants, as ‘high risk’ strategies (quotes are in the original 1985 paper), he then contrasts these ‘high risk’ strategies with population strategies (no need to bother with that quotes nonsense this time) which target the entire population, and aim to shift the entire population to the left — that is, move the bell shaped curve of the population distribution to the left, and in so doing lower the average behaviour — in the expectation that shifting the average, or mean value, will then drag the deviants in the tail, the obese and the excessive drinkers, also to the left.

This proposal, which Rose found very much to his liking, to target entire populations is of course pure healthism. But the whole doctrine behind population strategies is based on an astonishing leap of faith made most succinctly in a short paragraph (emphasis added) in the 1990 paper: “The results show [the link between the body and the tail of a distribution] to be a geographically world-wide phenomenon. It is hard to see how it could fail also to apply to temporal changes within a population, implying that changes in population characteristics will produce predictable changes in the size of the deviant subgroup”. Rose wisely adds, “This, however, requires confirmation,” — which as it happens, it still does today — but by then the payload had hit its mark. Whole swathes of public health doctors, the malfunctioning Mussolinis and the failed Pinochets, found the doctrine very much to their liking, for it gave them all they needed to go out into the world and pursue the relentless promotion of coercive healthism. The constant barrage of public health messaging to which we as an entire population are now routinely subjected is the inevitable result.

By now, dear reader, Dr No expects you will have joined up the dots. By far the bulk of our national response to covid–19 has been driven by public health doctors, the very same doctors who worship at the altar of coercive healthism, applied at a population level. We can see it clearly in the choice to adopt a population level approach to controlling covid — the population mean level of infection predicts the numbers of deviants (the old and the vulnerable, only they are spared that ghastly title in the public messaging) who get infected. We see the indelible stamp of coercive healthism in the demand that we all take steps to protect our health, regardless of individual risk, in an echo of the demand that we all cut down our drinking, even those who are at no risk from alcohol. We see it again in the instruction that we should all behave as if we have covid, whether we have it or not, a quite brilliant, Dr No has to admit, piece of covid zombification. And worst of all, we see the damage of social division between the zombie good, who follow the rules without question, and the deviant bad, who dare to question.

Just as, no doubt, the Mussolinis and Pinochets in their public health bunker plan their covid schemes and stratagems, crying Health for All, and All for Health, and ask of each other, what could possibly go wrong?

I agree, freewill with the individual’s autonomy intact should be upheld whenever possible.

However, what should be done about those who knowingly, or perhaps unknowingly abuse their bodies, but still have the expectation that the state, (through the NHS) will wave a magic wand over any illness (curing any disease) from making those choices?

Popular culture as such, encourages consumerism from every angle — the media is awash with it. Are they the true culprit? If so, what should be done?

Does Dr No assume that autonomous individuals are capable of not making the wrong choices? The counter argument to that is to look at how easy, with little resistance, it has been to turn rational thinking people into mask wearers, with very little evidence of their benefits. We are easily manipulated.

Education improves matters, helping us to make informed decisions. The problem is, when the educators have an agenda which we may not be made aware of. Then, it risks being state ideology.

James – however enticing the prospect, the sick should never never ever ever be blamed for being sick, and so should never ever be punished for being sick. This is an absolute requirement of humane medicine. Freewill includes the possibility that people make bad choices. You can’t have freewill, as long as you make the choices I/the state tells you to make.

To understand the importance of this, you need to think through what will happen if you blame people for their illnesses, and so for example punish them by withholding treatment. First off, who decides which illnesses are blameworthy, and which are not? Then where does it end? Say you are a sailor, and develop skin cancer? Clearly you are to blame, exposing yourself to all that extra UV in your hedonistic pursuit of a selfish pleasure. No treatment for you, boyo. Or you are black, and prone to sickle cell disease, so lets fix that one by sterilising all black people. This is the sort of thing the Nazis got up to. Don’t even think about going there.

Is it that modem civilisations, with their medical wonders and governing bodies are indeed meddling with the primal forces of nature?

Natural selection, survival of the fittest had no agenda other than that. It decided who would survive without moral obligation, judgment or baggage.

This has some relationship with Lord Sumption’s point that we currently have a strange / flawed relationship with death and risk of. We simply can’t save everybody, and nor should we in a world of increasing populations, consuming ever finite resources.

A more moderate and pragmatic view would be to accept life has risk, including death and that with personal responsibility (and choice) we can try and make the best of what we’ve been given by Mother Nature.

As sure as the sun will rise tomorrow, people will shuffle on and off of this planet! It’s unavoidable.

Ps. Where’s the outrage of 40m worldwide deaths from abortion, or over 1m from TB every year. All avoidable but we live with it. And so with that in mind, we need to give up our obsession with COVID and move on and live our lives.

Dr No,

For me the issue is not blame but who picks up the tab in a largely socialised healthcare system. There is surely a cohort of people who don’t look after themselves on the understanding that the rest of us will pay for their health care. A partial solution to this might be to align the tax take on products or activities that can be demonstrated as potentially harmful (smoking is the obvious example) with the overall cost of care and treatment. Then allow people to make their own choices.

‘Deviant’ is used here correctly as a mathematical term, not as a term to describe ‘bad’ people.

I was born with a natural tendency to challenge the status quo. Despite many years of schooling and many years of life on planet earth, try as I might, I can’t stop challenging the status quo.

Whilst this must be more than slightly annoying to some, it does seem to give one a way to see things somewhat differently.

For example, I don’t think people have free will. A statement which I know will be judged and challenged!

I do think we are all run by people who measure things. And this too may be challenged.

Whether it’s health, business, education or even the misunderstood money system, we are governed by people who measure.

This is dangerous at so many levels, for Doctoring, (and I’m not one), I as a patient found out about QOFs. I think this stands for Quality and Outcome Framework.

According to this website:- https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/articles/about-quality-and-outcomes-framework-qof

“The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) is a system designed to remunerate general practices for providing good quality care to their patients, and to help fund work to further improve the quality of health care delivered. It is a fundamental part of the General Medical Services (GMS) Contract, introduced in 2004”.

This is all well and good, and I’m pleased our doctors get rewarded for all their work but, who decides what should go into a QOF?

It seems to me to be one of those measurers who wield much power and not necessarily a lot of sense.

I can only assume, blood pressure is on my doctors QOF because as soon as I turn up which is not very often, they whip out a blood pressure cuff.

What with that and dolling out smarties, sorry I meant Statins, which I have declined, is it any wonder we are where we are!

Are measurers fascists? I don’t know, but measurers do in fact rule the world.

The underlying structure drives all things, especially once the measurers are involved!

Cheers

Alex – maybe, but it is not in common use in epidemiology, even if related terms (eg standard deviations) are. More to the point, the vast majority of readers of the BMJ are not mathematicians (so we might observe that when it comes to numeracy scores, mathematicians are deviants among the population of those who read the BMJ…) and so, while they might guess the term is being used mathematically, they will also get the message buried in the far more common use of the term. Rose has form on using words ambiguously eg the other example in the post, calling focused preventative measures a ‘high-risk’ strategy. Rose was not stupid, and must have know his terms were ambiguous.

Steve – you are right about the meaning of QOF, and many if not most GPs dislike it, considering it distorts clinical priorities, and only go along with it so they can get paid. It’s part of the tradition of paying GPs not just on a head count (number of registered patients) but also for doing X or Y, and that in turn has its roots in the ancestry of general practice, which goes back to the apothecaries and corner shop chemists, who sold items over the counter.

Nor should we forget the quote often attributed in various forms to Einstein but more likely first used by a sociologist, William Bruce Cameron: “However, not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” But numbers (counts, and percentages, which are based on counts) are both seductive and powerful to those who would control us and influence our behaviour, politicians but also the mainstream media; and so it is that we have QOFs, and a daily diet of numbers of covid tests, positives, admissions, deaths and more recently vaccinations.

Thanks Dr No for your reflexive post.

As a French MD, I’m receptive to your blog content.

Following the thought line of Steve, using mindlessly metrics can be problematic.

This is well explained in the book “The tyranny of Metrics“

“…move the bell shaped curve of the population distribution to the left, and in so doing lower the average behaviour…”

Classic unsane thinking. The assumption has been made that the “bell shaped curve” IS reality, and can be “shifted” much as one might move an armchair across a room.

Whereas of course the “bell shaped curve” is a pretty mathematical abstraction, which appeals precisely because it is so easily manipulated.

The only important question is “Does the mathematical model correspond to reality?” Or, better still, “How closely does the mathematical model correspond to reality?” Because it is “highly unlikely” that any simple mathematical model can ever correspond exactly to the multidimensional, almost infinitely variable world of reality.

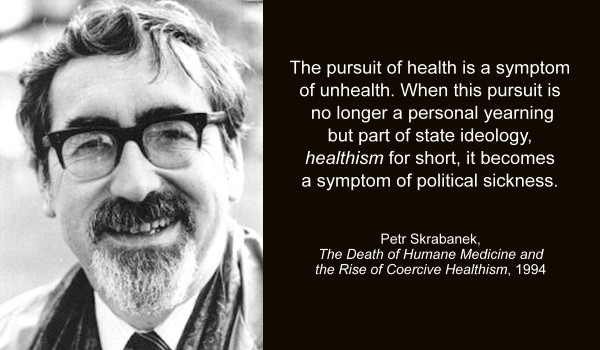

James – you might or might not appreciate another quote from Skrabanek’s The Death of Humane Medicine and the Rise of Coercive Healthism:

“Medicine is not about conquering diseases and death, but about the alleviation of suffering, minimising harm, smoothing the painful journey of man to the grave. Medicine has no mandate to be meddlesome in the lives of those who do not need it.”

There is also the medical principle under which Dr No practised throughout his career: “Thou shalt not kill; nor strive officiously to keep alive”. There’s more than just a hint of anti-healthism in the “nor strive officiously to keep alive” part.

Andy – fags and booze are already taxed hard, and Dr No has no general problem with this, although he does have a problem with minimum unit pricing for alcohol (discussed many times on the old blog), partly because it assumes Rose’s ideas work when they almost certainly won’t with something like alcohol. Moderate drinkers (at no significant risk) might cut down a bit, but the heavy drinkers will find the money one way or another, either from their food budget, or their children’s clothing budget. The important point is that individuals should be free to make their own (informed) choices, even when the outcome of that choice causes them (and even others, indirectly, eg the father who dies while his children are still growing up). Those choices may not be palatable in the slightest to others, but all the alternatives, which all in some shape or form have the authorities make decisions that individuals should be taking, are even less palatable.

JonBe – thanks, and thanks too for the interesting link.

Tom – indeed. It could even be said Rose did a sort of modelling thought experiment – and what could possibly go wrong? One of the more obvious flaws in Rose’s ‘model’, lightly touched on above, is that he assumes that all populations are one homogeneous interconnected population, where movement in one part will cause movement in another. But what if, for example, alcohol consumers fall into (perhaps many) separate populations: the teetotallers, the moderate drinkers and the heavy drinkers? Putting aside the minor trouble that, under Rose’s model, the teetotallers have to move to negative consumption (perhaps they start excreting alcohol?), if the populations aren’t connected, then there is nor reason to suppose they would move together. To extend your armchair analogy, there is no reason to suppose moving the armchair across the room should cause the dining table chair to also move across the room.

Dr No, by chance I happened upon a view of computer modelling from a professional statistician shortly after reading your excellent article. This extract may be of interest.

‘Absent knowledge of cause there will be uncertainty, our most common state, and we must rely on probability. If we do not know all the causes of the cure of the disease, the best we can say is that if the patient takes the drug he has a certain chance of getting better. We can quantify that chance if we propose a formal probability model. Accepting this model, we can answer probability questions.

‘We don’t provide these answers, though. What we do instead is speak entirely about the innards of the probability model. The model becomes more important than the reality about which the model speaks.

‘In brief, we first propose a model that “connects” the X and Y probabilistically. This model will usually be parameterized; parameters being the mathematical objects that do the connecting. Statistical analysis focuses almost entirely on those parameters. Instead of speaking of the probability of Y given some X, we instead speak of the probability of objects called statistics when the value of one or more of these parameters take pre-specified values. Or we calculate values of these parameters and act as if these values were the answers we sought.

‘This is not just confusing, it is wrong, or at least wrong-headed’.

https://wmbriggs.com/post/34533/

Tom – Briggs – a very interesting post, even if a little on the long side, and the prose not the most readable this side of Eden

An excellent quote Dr No you recite from Skrabanek! Thanks.

To home in on the most salient point: “…conquering diseases” – this objective is exactly what our leaders (scientists and politicians with the help of the state run media) have convinced us should be the right thing to do – in the response to the the cry’s of “something must be done!”.

Sadly, it will lead us to ruin, unless we / they come to our senses.

How wrong they are, and how right Skrabanek was.

Dr No you are on the money with this post. Surely Public Health Drs wake up every morning and can’t believe their luck: Not only are large swathes of the population following their every command, now they’re doing it whilst shouting ‘look at me doing as I’m told’. I think I can cope with the idea that we encourage the population to drink less but when that translates to people thinking I’m interested in the fact they’re doing ‘dry January’ then things have gone too far. Now I think about it I think that’s one of the things that makes me struggle with face masks so much, it’s such an in-your-face way of virtue-signalling.

“five fruit and veg a day”: I once wondered where that propaganda statement originated. A quick google took me to a writer who had devoted more time to the question. She traced it to a conference of Californian “produce” growers. That explained one mystery, to wit why there’s no reference to the benefits of nuts in the diet. Presumably the almond growers of California didn’t attend the conference.

I also came across a study, only observational of course, with actual evidence. It claimed that three, or perhaps four, was a sensible target.

Since my own consumption tends to fall in the range four to nine, I am pretty relaxed about what the best advice might be but am also appalled that governments pump out their propaganda based, apparently, on not a shred of evidence.

Still, I religiously follow Jeeves and eat plenty of fish. Sage fellow, Jeeves. Put in Australian, Jeeves was not a dill.

dearieme, I wonder if that good old traditional Australian dessert “flamin’ apples” counts as one or more of the “five a day”.

It’s always struck me as appetising – especially if you use some nice cognac to kindle the flames.

Is a Hot Cross Bun, with its load of sultanas, one of the five a day? I say yes.

I suppose that chocolate must be one of the five a day – it comes from a plant and is not a starchy cereal or tuber.

2 observations.

I am retired GP and worked on health committees (because I moaned about them so much I thought I’d best give it a go).

1. Public Health doctors are usually very nice people but have chosen their specialty for the rapid rise to consultant post and the 9 to 5 hours without patients. Also fits part time work v well.

2. Their name is brilliant: it means they are on all the top health authority committees and that the government will always look to them for advice rather than awkward clinicians.

(PS Skrabanek still rules OK, also James Willis and Raymond Tallis not forgetting Dalrymple. No evisceration of Covid policy by him yet, Dr No’s doing ok meanwhile).

Chris – Dr No thinks he remembers a public health doctor who (by her own account) used niceness as a weapon…

Healthy/safe/recommended upper and lower limits : alcohol is the real corker. Richard Smith, the ex-editor of the BMJ, once said somewhere (Dr No has still to find it, but as you will see that doesn’t matter) words to the effect that the the Great and Good on the 1987 committee that decided on the 21 units for men/14 units for women limits hadn’t got any real idea of what the real safe limits were, and so they picked those limits on the grounds they seemed like a good idea at the time, as they felt it unseemly for doctors not to have an opinion on the matter.

That this story is true (as is the ghastly implication, that when it comes to healthism, there’s no need to let an absence of proper evidence get in the way of setting a tight limit) can be seen from the this 2007 article from the Times (the wayback macine has an archived pre-Times paywall copy), and this frantic response from Smith in which he back-pedals faster than a circus uni-cyclist who has just seen Jaws come through the big top roof.

Apologies if I am repeating myself, Dr No, but have you read Tony Edwards’ slim volume “The Good News about Booze”? I read it at Christmas a few years ago and haven’t looked back. My wife and I actually began drinking regularly for our health!

Edwards provides many pages of citations, and shows very convincingly that “moderate” drinking seems to have significant beneficial effects against almost every disease. (Where “moderate” means between a quarter bottle and up to a whole bottle of wine a day, or an equivalent amount of spirits. Dry red wine is best, but the effect is there for white wine, whisky, brandy, etc.)

The funny thing is that the research has been done and is accessible, but everyone chooses to ignore it and go on inveighing against the demon drink. True, a whole bottle of claret every night is probably pushing it a bit, although its effects seem clearly positive. Splitting a bottle with a spouse or friend seems ideal, and dovetails nicely with Dr Kendrick’s suggestion (in “The Great Cholesterol Con”) that the French are healthier than might be expected because they eat in pleasant, relaxed, congenial circumstances.

“the 21 units for men/14 units for women limits hadn’t got any real idea of what the real safe limits were”

But they had the wisdom to use multiples of seven which would appeal to the remains of number magic beliefs held barely consciously by the population. They even managed to get a multiple of three in too. Bravo, boys!

dearieme – a pertinent observation on the numerology behind the limits!

Another less well known than it might be paper in the history of alcohol limits came from Dame Shelia Sherlock, the formidable hepatologist and professor of medicine at the Royal Free Hospital, where Dr No trained. In a review article on alcoholic liver disease (so lets be clear, she is not talking about other harms) in the Lancet in 1995 she wrote (emphasis added):

“Safe weekly limits are believed to be 21 units in men and 14 units in women. These figures may be too low; certainly little damage arises from 3 drinks a day, and there is some evidence that this level of consumption protects against coronary heart disease. 16 units (160 g) of alcohol daily for 5 years is probably the minimum associated with significant liver damage.”

No typos there: that’s 16 units – around 5-6 pints of beer, 2 bottles of wine or half a bottle of spirits – daily. Note that is to get significant damage; at lower levels of consumption you might get some (non-significant?) damage.

That didn’t stop Dame Sally Davis (CMO at the time) urging women a few years ago to ‘do as I do’ and think about ‘my risk of breast cancer’ while reaching for the corkscrew, adding that there is ‘no safe level drinking’, or a major study in the Lancet in 2018 concluding that (for all alcohol harms) ‘the level of consumption that minimises health loss is zero’. This may be statistically true, but what is its real world significance?

The key point – and this brings us full circle and so back to Skrabanek and healthism: any decision about ‘safe’ limits for something that has a J shaped risk curve, and has benefits as well as harms, is always political and, especially in the case of something like the ‘great and growing evil’ of ‘the demon drink’, moral. To pretend the chosen limit is defined by the science is pure hokum.

It is but a short step to argue, rightly or wrongly, that the legally imposed limits on social and economic behaviour in response to covid are not based so much on the science, as on political and moral – because moral judgements about the value of the quality and quantity of life are involved – decisions, and that to pretend these controls are defined by science is also pure hokum.

There is also “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” and similar syndromes.

One of the greatest weaknesses of modern medical and nutritional science lies in the assumptions made by almost everyone and hardly ever even considered, let alone challenged.

It seems that people can survive and be healthy on a meat-only diet, provided only that it contains plenty of fat. (That most people nowadays would find that gross is irrelevant; it’s just because of the way they were brought up).

Yet many people who eat only meat don’t supplement – not even with “vital” vitamins like Vitamin C. Yet they don’t get scurvy, or any trace of it.

Maybe Vitamin C is not vital at all, but is needed as an antidote to something else – such as mounds of refined carbohydrates?

Research on diseases presumed to be caused by alcohol may actually be due to refined carbohydrates and/or vegetable oils. In which case it may be safe to drink more alcohol than we have been given to believe.

The discouragement of alcohol reminds me of H. L. Mencken’s definition of puritanism: “The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy”.

Pure coincidence, but I found a piece by Richard North on the history of public health in England to be very interesting. He comes at it from a different perspective, but it dovetails nicely with your article here.

https://www.turbulenttimes.co.uk/news/brexit/brexit-in-the-shadow-of-louis-pasteur/