The Accidental Incidence Study

There’s not much to be said yet about the Pfizer vaccine study itself. It’s still early days, the case numbers are small, and there is still more than enough oppatoonity as they say Stateside left for it to fall over. But hidden within the interim results released last week is a rather interesting accidental study, which does bear having something said about it. Though not set up as such — and normally this would be a serious objection — the study is, in its placebo arm, as near as can be to a prospective covid–19 incidence study. Healthy patients have been enrolled, and assiduously followed up for months, to see, among other things, whether they develop covid–19. That is exactly what a prospective incidence study does. What does the study so far tell us about covid–19 incidence, and how does the study’s incidence compare with other estimates? Might we at last get a better idea of real incidence, and so a better idea of whether we are over or under reacting to the pandemic?

The numbers that interest us here are the total number of patients fully entered into the study and followed up, and the number of cases of covid–19 detected among this group: 38,955 and 94, respectively. Since the trial used a one to one allocation to vaccine or placebo, that means we have around 19,478 people in the placebo arm; and since we also know the interim efficacy was 90%, we can allocate the 94 cases to the two groups to get that 90% efficacy. If there were 85 cases in the placebo group, and 9 in vaccine group, that gives us an efficacy of 89.4%, which will do. This gives us a crude incidence over the three months or so of the trial of 0.4%. If we then say there are 100 days in three months, that gives a daily incidence of 0.004%, or 40 cases per million per day.

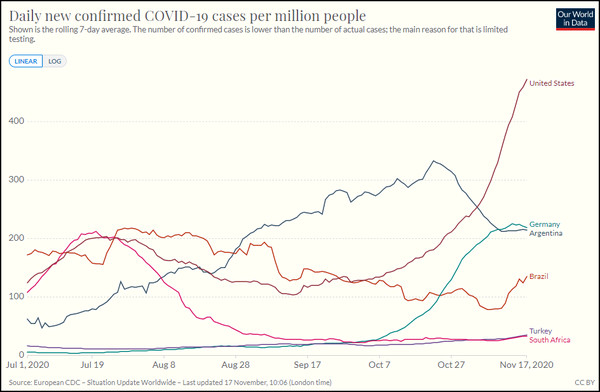

Now for the interesting question: how does this compare to other incidence estimates for similar populations? Here Dr No came across the first hurdle: where was the study conducted? Mainstream media reports have breezy references to six countries, but apart from the unsurprising inclusion America and Germany, no other country specifics are forthcoming. Not only did the MSM not care, they weren’t sharing either, leaving Dr No hurting. Nor does the 147 page study protocol contain any hint of the other countries. The information is buried deep in a US clinical trials registry, under Location (click to expand the section on the webpage): loads of US sites, half a dozen or so German sites, plus a handful in Argentina, Brazil and South Africa, and ten in Turkey. Turkey? But it makes complete sense once you know the CEO of BioNTech SE, the German company developing the vaccine with Pfizer, is of Turkish descent. Nonetheless, the study is overwhelmingly American, with around 130 of the 155 sites located in the US. Let us get some daily case data for these six countries:

Figure 1: Seven day moving average daily new cases (test positives) per million population of covid–19 in the six countries in the Pfizer vaccine trial from 1st July to date. Source: ourworldindata.org. For the record, the UK has been running at about 330 daily cases per million over the last couple of weeks, but rates were much lower in late summer.

Now we have to do a bit of mark one eyeballing here, and judge what we think is a near enough summary rate for the countries and period shown. Bear in mind what we are looking at here is incidence: new cases, not current cases, which is prevalence. Dr No suggests that for the United States it is approaching 200 daily cases per million population. If we factor in the other smaller countries, then maybe around 150 daily cases per million population. Let’s say 175 daily cases per million population.

This is over four times higher than the estimate of 40 daily cases per million given by our Pfizer Accidental Incidence Study. And yet, as Our World In Data point out, along with countless hand wringers and bed-wetters, cases defined by PCR test positives are supposed to under-estimate true cases, because of limited testing. Others, Dr No included, suggest that PCR tests are too sensitive, and so over-estimate cases, and it appears the routine daily cases are over-estimating cases, substantially — or alternatively, the Pfizer study is substantially under-estimating cases? What on earth is going on?

The first thing to note is neither the Pfizer AIS (Accidental Incidence Study) nor the regular daily counts are random samples. The latter until very recently have been largely driven by people developing symptoms, and then being tested, so there will be selection bias, as in the people selected for testing are more likely to be infected. More recently that has changed somewhat, as countries do more routine screening. Recruitment to the Pfizer AIS sits somewhat under a shady tree, but so far as can be told from the protocol, the inclusion criteria can be summed up as generally healthy non-pregnant (a routine exclusion) people aged 12 and over, with at least 40% being over 55 years old, and between 30% and 42% from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds. The recruitment process itself is not clear, but we must presume it is voluntary, and so more likely to include civic minded folk. Nonetheless, if anything, it is likely to be more random than the routine country by country case counts, with a possible selection bias towards racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds.

The second important consideration is case definition: what makes someone a case? For the national counts, it is, in effect, a positive test result, with or without antecedent symptoms. Dr No and many others have cautioned against this practice, since it risks creating a testdemic when the test is over-sensitive, as indeed PCR tests are. Cases in the Pfizer AIS are chiefly counted at ‘Unplanned Potential Covid–19 Visits’, which happen whenever potential COVID-19 symptoms are reported. These ‘unplanned…visits’ (which are of course planned – they are in the protocol) include a nasal swab test, to confirm or refute the diagnosis, so the case definition is covid symptoms plus a positive test result. This is a slightly stricter, and if anything more realistic, definition than that used in the routine daily counts, which include asymptomatic as well as symptomatic test positives as cases.

The last consideration is person-days of exposure: not all participants were entered on day one of the trial. The data for this is not yet available, and so we shall have to wait for it, and it will increase the cases per day per million (because there are less person-days of exposure), but by how much? If we assume a steady increase over the trial period of enrolled participants, then maybe by a factor of two but that still has the Pfizer AIS estimate of incidence substantially lower than the national daily count estimates.

Of the two data sets, the Pfizer set is by far the better. By accident rather than design, it has nested a true prospective incidence study within its vaccine trial. Subjects — the all important denominator — are known, and they are actively and rigorously followed up, for months, and then years, another essential requirement for a high quality study. Assuming no exceptional selection bias, and there appears to be none, except perhaps towards ethnicity, then the Pfizer study amounts to the best, though still far from perfect, estimate we have of the true incidence of covid–19 in the population. If that is the case, and Dr No thinks it is, then many governments, including our own, are guilty of wildly over-estimating cases — four fold? ten-fold? — and in so doing have created not a pandemic, but a testdemic. It is time to remember a wise old principle of medical practice: you treat the patient, not a test result.

Editor’s note: penultimate paragraph added 09:55 on 18th Nov 2020.

Editor’s note: penultimate paragraph added 09:55 on 19th Nov 2020.

Good to see Dr No’s Tardis is in fine fettle :-) !

It must be that sonic screwdriver fiddling with the settings again! Now corrected…

Oh, I’m so liking this line of enquiry, Dr. No. Thank you.

“…there is still more than enough oppatoonity as they say Stateside…”

I don’t think I quite recognise that long word. Did you by any chance mean to write “ahppadoonidy”?

Seriously, it is very reassuring to see something approaching solid, reliable data at last.

I take it for granted that the authorities in Western countries at least are doing everything in their power to make the epidemic look as bad as possible. That, they hope, will prevent them from looking such consummate fools.

Won’t the trial results be affected by natural T cell immunity from other virus which evidently is high, and acquired immunity from those who were in contact with the virus but were asymptomatic or had unnoticed symptoms? Such individuals cannot except by chance be evenly represented in the two cohorts, nor such immunity evenly distributed in different population groups. Could the vaccine group perhaps have a higher number of natural or acquired immunity individuals?

Wouldn’t a better trial be to expose two groups to infectious individuals? There still remain a lot of people in the placebo group who did not get CoVid.

And… in my career in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, I was always told, trial results were never evaluated until the trial was over to avoid being misled about efficacy and possibly bais to the rest of the trial.

Tish – thanks, but important caveats – see reply to John B below.

Tom – an ahppadoonidy by any other name would smell as sweet.

John B – the whole immunity thing is something of an unknown at the moment, T cells very likely very important, and cross immunity from other coronaviruses to SARS-CoV-2 is plausible but not yet proven, and certainly some study participants will most likely have had asymptomatic/unrecognised covid infection and so immunity but that’s what randomisation is for: unrecorded variables that might influence the result should be randomly spread across different groups, and you normally do some checks, looking at things you can measure eg bloods or whatever. That said, the protocol suggests (page 73), though it is a bit ambiguous, that serology for prior covid infection will be done on all participants at the screening visit (“Collect a blood sample (approximately 20 mL) for potential future serological assessment and to perform a rapid test for prior COVID-19 infection.” [emphasis added, the ‘and’ suggesting the test for prior infection will always be done ie should be read as “Collect a blood sample (approximately 20 mL) for (1) potential future serological assessment and (2) to perform a rapid test for prior COVID-19 infection.”]).

Also important to remember this (simple) analysis presented here is unconventional. It goes against the principle of only using study data for pre-determined analysis (ie no post hoc data dredging) but that said I think it is valid, with the strength that it is inherently a good incidence study even if it wasn’t set up to be one. The main weakness is in the paragraph I forgot to add first time round, the person-days of exposure, which will be less than I have assumed, and with the denominator lower, the rate will go up.

It is also an interim analysis, in that the data is not fully complete yet, but I think that too is OK because we are just looking at one very simple thing, how many in the placebo arm developed covid-19. When it comes to trials (and so commercial interests) which is what the study is designed to be, then there is a huge risk of interim result leading to jumping to $$$$$$ conclusions (which is rather what is happening right now) hence no interim analyses, but on the other hand if there are striking benefits (or harms) in the interim data then it may be unethical to plod on with the trial regardless when you already have sufficient evidence of benefit (or harm), so a case can be made for interim analyses. Naturally the company doing the trial will see such an announcement as a great oppatoonity to whet appetites should the interim analysis be positive…