A Put Down for The Lockdown

Back in the 1980s, John Naughton, The Listener’s TV critic at the time cracked Norwegian after hearing a recording in English being played backwards and forwards. Norwegian, he realised in an instant, is merely English spoken backwards. On forwards, clear English could be heard, but in reverse, the machine delivered perfect Norwegian. Recalling Naughton’s discovery 35 years later, Dr No realised that must also mean that English is merely Norwegian spoken backwards, and that this might be the way to get at the contents of a promising covid–19 report published in Norwegian by Norway’s official Public Health Institute. Alas, the Folkehelseinstituttet report spoken backwards doesn’t come out as English, but on another level it is ‘English spoken backwards’, insofar as it’s main conclusion is the reverse of English lockdown dogma. The Norwegians, after due analysis, have all but concluded that the science, to date (and that is an important caveat), does not back hard lockdowns.

Dr No has already pointed out in a previous post that falling for the post hoc fallacy is nothing short of scientific imbecility. It is meaningless to say we had a hard lockdown, and then covid–19 incidence fell, so the hard lockdown must have caused incidence to fall. Of course it might have been cause and effect, but it is equally possible that some other factor cause the incidence to fall. There are plenty of possible candidates, ranging from a seasonal effect (summer causes respiratory viral infections to decline, ie it has nothing to do with what we do), through spontaneous decline (that’s just the way the cookie crumbles, ie randomness), to voluntary soft lock down and informal social distancing are sufficient to reduce transmission (ie what we do does have an effect, but we do not need to burn down the house to eliminate the mouse).

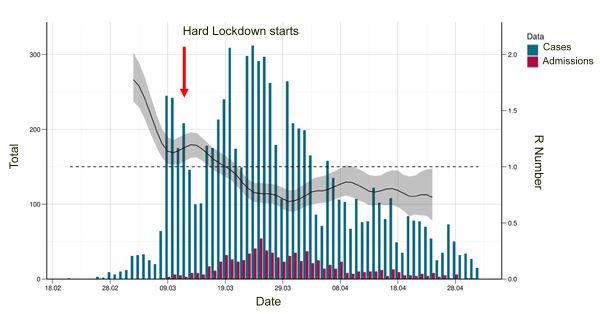

Britain’s hard lockdown was triggered by Professor Meltdown’s hysterical modelling and, it now seems increasingly likely, AC/DC’s (because he travels both ways) nudging at SAGE meetings. None of this is science. In contrast, the Folkehelseinstituttet report contains an analysis of actual data, and it shows, crucially, that the R number fell in Sweden before it introduced its hard lock down. In the following chart, taken from the report, the R number (grey line, with confidence intervals) falls sharply to just over 1 on the 9th March, and by 20th March was below one, and has stayed there ever since. The Norwegians introduced their hard lock on 12th March:

Figure 1. Norwegian covid19 epidemic: Number of covid-19 cases reported MSIS (The Norwegian Surveillance System for Communicable Diseases) by sampling date, number hospitalised with covid-19 as the primary diagnosis by hospitalisation date, and Re estimated by the EpiEstim method by date. Source: MSIS and the Norwegian Pandemic and Intensive Care Register.

This replaces a post hoc fallacy with what we might call pre hoc certainty. Given the lead time for a hard lockdown to have an effect, we have to conclude, on the basis of this analysis of real data, that the hard lockdown did not get the R number below 1. It may or, more likely, may not have helped keep it there — only further analysis will determine that — but it cannot have caused the initial steep decline in the R number.

The report concludes (this is google translate’s attempt to speak Norwegian backwards, as tweaked by Dr No to make if read more like English spoken forwards, with emphasis added):

“This [first] wave of the covid-19 epidemic in Norway is past the peak and declining. That’s because of a combination of measures…but it is not possible to point out which measures have been the most important and sufficient to get the epidemic under control. It looks as if the effective reproduction rate had already dropped to around 1.1 by 12th March, when the most comprehensive measures were implemented, and that subsequently didn’t take much to push it down below 1.0.”

The Norwegians are commendably transparent here: they make it clear they do not know what did cause the fall in the R number, just that it appears it cannot have been a result of the hard lockdown, because that only happened after the R number had already fallen. In an interview with NRK, the Norwegian state owned broadcaster, Camilla Stoltenberg, the director of the Institute of Public Health said, “The academic basis [for the hard lockdown] was not good enough,” adding that, “Our assessment now…is that one could achieve perhaps the same effect and avoid some of the unfortunate effects of hard lockdown by not closing, but by keeping open with infection control measures.” Future waves, if they occur, should, Stoltenberg said, be managed using “gentler and more flexible measures.”

Hard lockdowns are — and this is hardly a strong enough word to use — devastating, and that from the cradle to the grave. Economies are ruined, education is wrecked, careers are blighted, businesses are destroyed, lives are lost, and health is compromised. The people — and what is man if not a social animal — are driven into mutual fear and isolation. The dying die alone, and the survivors are deprived of the chance to kiss the cool forehead of the dead. It is impossible to exaggerate the cruelties of hard lockdowns. Lockdowns that, the science now suggests, have been imposed in vain, by the vain.

It’s refreshing to learn that the Norwegians appeared to have been more open and honest and to some extent inconclusive in their findings.

But as you suggest, that is much better than the Blighty approach — to seemingly dither, panic, slam the brakes on and deny all wrong doing, or faltered decision making.